Breaking the Elite Extraction–Control Nexus: Three Institutional Reforms

Without meaningful institutional reform, Nepal will continue to relive its periodic collapses.

Breaking the Extraction–Control Nexus

Nepal’s elite power thrives on two reinforcing mechanisms: extraction (taxes and rents --bribes) and control (immunity through institutional capture). To break this nexus, reforms must begin by freeing the three primary pillars that guard Nepal’s democracy — the Anti-Corruption Body, the Election Commission (whose duty goes beyond conducting elections to enforcing constitutionally mandated internal democracy -- Article 269(4)), and the Presidency–Upper House nexus, both of which are manipulated through the Lower House math to perpetuate elite dominance under undemocratically run party bosses.

Before presenting the three amendment proposals, this essay first lays out a framework to understand how Nepal’s political machine has managed to tighten its stranglehold on the state and society — by manipulating institutional mechanisms and erecting structural barriers that shield its members from accountability and criminal prosecution.

The Cracks in the Machine

Nepal’s Gen Z uprising in September shook the country’s political machine — its three-decade-old legacy of control and manipulation — down to its core. It took barely seventy-two hours to expose what had been festering for years: a deeply embedded system of elite overproduction and mass immiseration.

What began as the Arab Spring in Tunisia in the early 2010s — a wave of uprisings against corruption and economic stagnation — swept through Egypt, the Philippines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and beyond including the recent one in Madagascar. In many cases, the ruling executives had to flee the country –Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Madagascar. A similar movement just shook Nepal’s thirty-year-old political system.

For decades, the grip of elite power had been visible yet unchallenged. Despite public anger and media outcry, the old game went on — unmoved and unrepentant. The regimes kept rotating among the same players; corruption soared and enveloped society with impunity. Despite the uproar and recurring dysfunction, the political machine kept churning. How?

This essay explains how elite power was sustained and protected through two mutually reinforcing mechanisms — extraction and control — what I call the extraction–control nexus. This essay also offers three institutional reforms to break this chain.

The path to reform, I argue, must begin by freeing the three captured institutions:

The Anti-Corruption Body,

The Election Commission, which must enforce internal party democracy rather than merely conduct elections, and

The Presidency–Upper House nexus, both of which have been manipulated through the Lower House electoral math to entrench elite dominance.

The extractive activities that generate resources — symbols of a pervasive and corrosive society — are largely protected by institutional design stacked by the loyal elites. We already know the symptoms: corruption, dysfunction, and loss of public trust — the very triggers behind the Gen Z uprising. But treating the symptoms is not enough. The root cause lies deeper. Reforming the institutional architecture itself is the only way to reduce these corrosive symbols and strengthen governance from within. A brief description of the three institutional reforms are presented below with links to expanded versions published on the platform – Nepal Unplugged.

The Extraction–Control Nexus Explained

In a nutshell, Nepal’s elite power rests on an extraction–control nexus: siphoning wealth from society (extraction) while manipulating institutions to ensure impunity (control).

The elites extract taxes from the public to sustain an institutional apparatus that employs loyal bureaucrats and party elites — dispensing perks, privileges, and positions, including seats in the Upper House, the Presidency, proportional parliamentary memberships, and oversight bodies.

At the same time, they extract rents — through bribes, kickbacks, and license deals — from the same society to finance a cadre machine below, ensuring loyalty and mobilization.

This dual stream of extraction nourishes the royalized elite at the top while maintaining an obedient political base below — a self-reinforcing cycle of extraction and control.

1. Extraction: The Wealth-Pump Economy

To maintain its power machine, Nepal’s ruling elite has long extracted resources from society through taxes, bribes, and remittances — a system I call the wealth-pump economy.

The major political parties together command a vast cadre base, numbering around five million. They compete for nearly 30 000 political positions across the federal, provincial, and local levels — each requiring enormous sums of money to contest and maintain.

To fund this machinery, the parties depend on bribes, kickbacks, and licensing fees. Meanwhile, a vast portion of Nepal’s able-bodied youth fuels the remittance economy, sending money home that floats the national economy — and, indirectly, the elite lifestyle itself.

Add to this a layer of NGOs, business ventures, and remittance-backed industries and customs operations, and the result is a system where the rewards of extraction flow upward, while ordinary workers abroad shoulder the burden.

Through these channels — both legal and illicit — the elite keep their political operations alive and their privileges intact.

2. Control: Institutional Capture

The second mechanism is control — the capture of institutions designed to keep power in check. This “corruption machine” operates through a tightly woven web of influence across three interconnected pillars: the Presidency, the Upper House, and the lower-house math that dictates electoral outcomes.

The elites deliberately crafted the constitution to make these bodies mutually dependent, allowing control of one to guarantee control of all.

Once a party captures the Lower House, it uses that numerical advantage to dominate the Upper House and negotiate control of the Presidency. These upper institutions are then used to reward loyalists and consolidate dominance.

Both the Presidency and the National Assembly are not directly elected by the public, enabling party elites to fill them through bargaining rather than merit. They also use lower-house power to pack the Anti-Corruption Body with loyalists — insulating themselves from scrutiny. Likewise, they manipulate the Election Commission to look the other way on constitutional violations such as the lack of internal party democracy. Even the proportional and quota seats — meant for inclusion — are auctioned to cronies and the highest bidders.

Through the institutional capture of these three bodies, the elites shield themselves from prosecution while perpetuating a closed, self-serving loop of political control.

3. The Dual Strategy of Power

This dual strategy — extractive resource generation coupled with institutional protection — has enabled Nepal’s elites to sustain their dominance for three decades. It explains how the system survives every scandal, reshuffle, or “reform” cycle, always resurfacing under new labels but with the same players.

Yet the Gen Z uprising has revealed a historic opportunity to break this cycle. The next step is to target the three captured institutions that hold the key to renewal.

The Uncertain Path Ahead

There is much uncertainty ahead as Nepal stands between elite regrouping and voices for party renewal. Unanswered questions remain — such as those raised in the New York Times investigative article — about the nature of the destruction and arson that occurred on the second day of the unrest (September 9). These incidents must be thoroughly investigated and the perpetrators held accountable.

Meanwhile, the leaderless movement of Gen Z will need time to navigate its own identity and direction. But regardless of these unfolding dynamics, certain reforms cannot wait. They must be addressed with urgency before the same cycle of capture and decay resets itself once again.

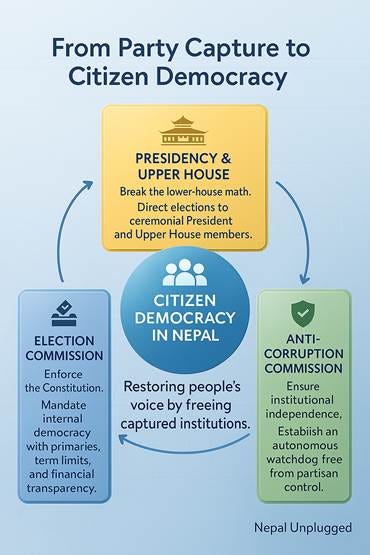

Toward Reform: Fixing the Three Captured Institutions

If Nepal is to move beyond the era of extraction and control, reform must begin at the heart of institutional capture — within the Anti-Corruption Body, the Election Commission, and the Presidency–Upper House nexus. Each, with the right reform, can turn from a pillar of protection into a pillar of democratic renewal.

1. Independent Anti-Corruption Body

As I have argued in Ungreasing the Wheels of Corruption, Nepal’s anti-corruption commission has been systematically politicized — packed by the same forces it was created to oversee. To restore trust, it must be structurally independent from political appointments, with transparent asset audits and citizen oversight. Only a truly autonomous body can expose and dismantle the patronage networks that sustain elite immunity. For details with examples from other countries: https://nepalunplugged.substack.com/p/ungreasing-the-wheels-of-corruption?r=2diukz

2. Internal Party Democracy: The Party Bill of Rights

The rot begins inside the parties themselves. In my Party Bill of Rights proposal, I called for the Election Commission to enforce the constitutionally mandated internal democracy outlined in Article 269(4)(a) of the Constitution.

Everyone praises the Commission for its efficiency in conducting periodic elections, but that is only half its duty. Its deeper constitutional responsibility is to ensure that political parties themselves operate democratically — through primaries, transparent financing, and leadership rotation. Without this internal reform, Nepal’s politics will remain a closed circle, recycling the same elite under the façade of democracy.

Internal party democracy is not procedural — it is the foundation of representative legitimacy. For details: https://nepalunplugged.substack.com/p/nepals-september-reckoning-why-a?r=2diukz

Constitutional Mandate: Nepal’s Constitution (2015, Article 269(4)) clearly states that for a political party to be registered, it must fulfill the following conditions:

(a) its constitution and rules must be democratic,

(b) its constitution must provide for election of each of the office-bearers of the party at the Federal and State levels at least once in every five years; provided that nothing shall bar the making of provision by the constitution of a political party to hold such election within six months in the event of failure to hold election of its office-bearers within five years because of a special circumstance.

(c) there must be a provision of such inclusive representation in its executive committees at various levels as may be reflecting the diversity of Nepal.

Yet, one wonders why the Election Commission (EC) never tried to enforce this clear constitutional mandate.

Perhaps two reasons:

a. The EC board is stacked with political appointees.

b. The clause itself is vague—lacking specifics like primaries for all seats, term limits, financial transparency, and inclusivity.

It may be time to consider an Independent Citizen Democracy Tribunal (ICDT) as a watchdog—to ensure parties serve the public interest, not operate as private clubs.

Like in South Africa, I also wonder if a citizen group could bring a case against the EC in the Supreme Court for skirting its constitutional duties.

3. Presidency and Upper House Reform: Breaking the Leviathan

As detailed in Shackling the Leviathan, the interlocking control among the Presidency, Upper House, and Lower House must end. Nepal needs a directly elected President and a restructured, regionally representative Upper House to restore the checks and balances envisioned by the Constitution but never realized. Separating these centers of authority would finally break the culture of back-room bargaining and dynastic monopoly. For details: https://nepalunplugged.substack.com/p/shackling-the-leviathan-through-constitutional?r=2diukz

From Capture to Renewal

These three reforms — (1) an independent Anti-Corruption Commission, (2) democratic political parties with primaries, term limits, and financial transparency enforced by the Election Commission, and (3) directly elected, independent bodies for the ceremonial Presidency and the National Assembly — form the foundation of what I call “Game B Democracy.”

It is a system that rewards transparency, merit, and accountability over patronage, control, and manipulation.

In essence, an independent anti-corruption body can curb grift and the illegal flow of money toward the cadre machine. The Election Commission’s enforcement of competitive primaries, transparent party finances, and fair allocation of proportional and quota seats would reduce the elite’s top-heavy loyalty and reward system. Finally, competitive elections for the ceremonial Presidency and the Upper House through the direct election can dismantle the entrenched culture of collusive horse-trading and favoritism that has long distorted Nepal’s democratic institutions.

Especially, the argument for a directly elected ceremonial president is to ensure that, in times of crisis, the head of state can rise above partisan interests — unbeholden to party leaders who selected them and unafraid to stand up to the Army — guided solely by the duty to safeguard the nation and its democratic ideals above all else.

The Gen Z generation has already cracked the surface of the old order. The next step is to rebuild the institutional soul of Nepal’s democracy — from capture to renewal.

*****************************************************************

About Author: Dr. Alok K. Bohara, Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of New Mexico, writes as an independent observer of Nepal’s democratic evolution as a system viewed through the lens of complexity and emergence science—critical of capture, wary of populism, and steadfast in his belief that accountability and citizen trust form the foundation of a resilient and prosperous republic. Bohara1955@gmail.com